Imagine a petrified editor[i] awaking from a recurring nightmare, with the taunting and looming idea that they will soon be replaced by AI. Exaggeration? Maybe. But come along; we’ll figure this out.

An editor from yesteryears (say, around late 1990s, to be precise) will tell you how rapid the process of evolution can be—at least in the IT-enabled editorial landscape. Understanding this journey is really a cinch: a bit of simple imagery is all that it takes to underline the impact of changing times on the proverbial editorial desk. Imagine one such desk from the ’90s, and this is what you may find:

-

- A physical manuscript, lying at the center

- A pencil, sharpener, Wite-Out, and an eraser, surrounding the manuscript

- A few color pens (yes, some did use them quite effectively)

- Paper clips and a (half-used?) pack of Post-it® Notes

- The current editions of Merriam-Webster, Chicago, and a host of other subject dictionaries and style guides (all in hard copy)

- A landline (select the make of your liking—though probably a corded landline!)

- And most of all, the typical smell of paper (that’s certainly not on but draping the desk)

Did I miss anything? Probably, but let’s move along.

Now, turn your focus to the present day: Do these items start disappearing one after another—like Alice-style Cheshire Cat (never to reappear)? No surprise.[ii]

Okay, it’s time to fill back the desk: Whoosh! Here comes the laptop, (maybe) a wireless mouse and keyboard accompanying it, a mobile phone and charging dock, earphones, additional monitor(s), and other signs of the modern era. Post-it Notes may still be lurking around; thank goodness for this tiny source of paper smell surviving to this day.

What do you think has changed the look and feel of our editorial desk? You’re right: technology!

Before going further, consider this common myth: Editors are generally averse to technology robbing their workspace.

This myth originates in the technocrat’s oversimplifying view of the editing process. And the editor expects the technocrat to be—realistic! That said, let’s find out realistically where we started from, where we stand today, and where we aim to go.

- Technological Evolution of Editorial Processes

As authors and editors migrated away from hard copy, the technological evolution started with a simple word-processing application. Instead of taking out all of those color pencils and Wite-Out, you would:

- Open the author’s manuscript (an MS Word file) on your computer.

- Set the Track Changes on.

- And off you go!

Identifying manuscript elements was streamlined using intelligible tags (<Title>, <AU>, <Aff>, <H1>, <Fig_Cap>, etc.), and editors began to enjoy all available features of MS Word: search and replace, wild-card patterns, autonumbering, list formats, developing use-and-throw macros, and so forth. Having the content edited in Word simplified things for the typesetter, too, and we began to see reduced timelines with fewer introduced errors.

While Word largely catered to authoring nonmathematical journal articles and books, the humongous math-heavy scientific publishing space mostly relied on LaTeX. Thus, hard-copy editing was here to stay—for some time more.

Before tech gurus could offer a WYSIWYG solution to editors for LaTeX manuscripts, they found an intermediate workaround: WinEdit. This interface required the editors to have a great deal of understanding of LaTeX code. Not much time elapsed that there was a “true” WYSIWYG solution to the LaTeX system: BaKoMa.[iii] The Word-like interface of BaKoMa encapsulated all “scary” technical details of LaTeX code and presented on the fly the expected output of the code to the editor. You simply edited the content as you did in Word, and the system generated the corresponding LaTeX code in the background.

By this time, hard-copy editing was gasping for its last breaths, ushering in the days of “hard copyediting”—for some.

- What Do We Have Today?

Rather than being resistant, editors today (mostly) appreciate that the broad range of automated routines/tools available to manage mechanical aspects of their task leave more time at their disposal to focus on subjective aspects.

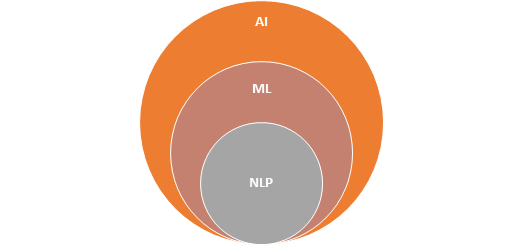

The progress doesn’t stop here. With recent advancements in NLP (natural language processing) and ML (machine learning)—two key subsets of AI (artificial intelligence)—editorial tools have been mounting new heights, though still very far from the summit. NLP, ML, and AI are often used interchangeably. To offer better clarity of their interrelation, I use below a simple Venn diagram and explain how each contributes to the big task:

- NLP helps computers/machines understand the human language.

- ML trains machines to learn automatically and improve from experience.

- AI, the “Big Daddy,” uses

- NLP—to understand the user’s intent;

- ML—to deliver an accurate response.

This is certainly an oversimplified explanation. If you’re a complete novice and interested in gaining a good conceptual grasp of these fields, I strongly recommend this easy-to-understand MonkeyLearn blog post.

From the editorial perspective, NLP is the most critical facet that merits further exploration. In order to “understand” text, NLP performs syntactic analysis and semantic analysis.

Syntactic analysis deals with breaking down the text into various categories and labeling them for further processing at the semantic analysis stage. Semantic analysis is entrusted with the daunting task of capturing the meaning of text—based on the relationship of various parts identified at the syntactic analysis stage—within the given context. I’ll come again on the topic of context in the next section.

Alexa, Siri, and Google Assist are a few popular examples of NLP application from everyday life. However, for the discussion here, the most relevant one from the editorial standpoint is Lumina’s proprietary tool EditRite. It is a manuscript assessment and classification tool, particularly designed for assessing journal articles for use of language. EditRite reads the content and understands the context to report grammatical errors. There are four main rule categories covered in the tool:

-

- Grammar

- Punctuation

- Spelling

- Style

That’s about the current status of technological “intervention” into the editor’s life.

- Where Do We Go from Here?

No, I didn’t pick this line from the Evita song. Just a coincidence.

Okay, back to the discussion. You must have noticed the emphasis placed on the term context in the previous section. That’s the key to the future—of NLP and, by extension, AI. Our present-day bots are limited in their ability to understand human context, which is as large as the universe is known to humankind.

Let’s narrow down the problem statement to the task of assessing the use of language in a manuscript using an NLP-based tool/application. All current tools evaluate one sentence at a time, and their understanding of context is limited to that very sentence. Now hold that thought: I want you to read the last sentence one more time, because it refers to the boundary wall we need to demolish to expand the territory of technological evolution.

It is worth appreciating that it takes more than a thousand NLP rules and a large database of information to process the level of details necessary to decipher the context of a single sentence and offer relevant solutions or suggestions thereon. Now, extend the scope of context building to two or three sentences (or, say, a short paragraph) at a time: the semantic analysis requirements shoot up exponentially. Indeed, our present-day bot would have a “nervous breakdown” at the very “thought” of expanding the context to include the whole manuscript at a time, in order to offer suggestions on each successive sentence of the manuscript. Phew—let’s cool it down here.

By now, you must have sensed what it takes to develop a true contextualized language application, particularly to support editorial effort. That is the road to the future.

Conclusion

Technology creates more employment opportunities than it destroys,[iv] thus these advancements shouldn’t worry a forward-thinking editor. Our current technological success in deploying facets of AI for building effective editorial tools marks the fact that we’re headed in the right direction. The current success is underpinned by the increased cooperation between technocrats and language experts. There is a growing need to take this cooperation to the next level: that is, marry the skills of a linguistic scientist with that of an AI expert. This new breed of professionals will bring about a paradigm shift in the game. And then, reaching the summit is just the matter of time.

Interested in learning more about Lumina Datamatics’ copyediting services? Email our team to learn more about how to copyedit educational content or to request a quote. You can also visit our website to learn more about Lumina Datamatics.

SOURCES:

[i] Throughout, I’ve used “editor” synonymously with “copy editor” for the ease of readability.

[ii] It’s worth noting that even in today’s digital era, some authors, publishers, and disciplines still gravitate toward hard-copy manuscript. While those files can be converted to digital, they are not my primary focus in this article.

[iii] Unfortunately, the link to the BaKoMa website is not secure, so I desisted from adding it here.

[iv] I’m stating this as a personal belief, not as an established fact. You may disagree with it. So let’s say it is debateable, in all fairness.

0 Comments