RIP Snow Days

In 2005, when Hurricane Katrina devastated the city of New Orleans, it displaced an entire school system, leaving tens of thousands of students without access to education. The State of Louisiana responded by working with a coalition of private e-learning companies and charter academies to embrace online learning as one way to help bridge the gap until schools could be repaired, and students could return to the classroom. Similarly, in 2012, when Hurricane Sandy battered the NYC region, resulting in massive displacement of their student population, New York City Schools responded to the emergency by launching an e-learning initiative that would allow their student population to continue their education through virtual classrooms. But in 2020, when the Covid-19 global pandemic reached American shores and closed schools and universities across the country, the conversation looked quite a bit different, with everyone from The New York Times, Forbes, Wired, Medium, CNN, and many others putting forth their own opinions and predictions about what was in store for students.

Something we can all agree on is that the discussion around the role of online education has changed. What was once considered a life raft during times of emergency is now being recast as a central pillar. If the pandemic fundamentally changes our approach to public education, causing it to much more closely align to blended learning models that fuse in-classroom experiences with online learning, one question inexorably follows… Is this model of education available to everyone? Is it truly “accessible?”

Accessibility, in this context, means that the tools we use for online teaching are developed with inclusivity in mind, so that they can be used by as many people as possible, including those with impairments or disabilities. Designing a program from the ground up, with the intention to allow universal access to the greatest extent possible (i.e., adhering to the tenets of universal design leaning, or UDL), should be the goal of all virtual learning programs. This “ground-up” approach is preferable to retrofitting existing materials to meet accessibility guidelines.

Due to the sudden and unexpected nature of the COVID-19 crisis, many institutions attempting to ramp up their online offerings quickly have a limited budget, and as a result, may be more likely to turn to OERs. As these institutions build their fall course materials, they must also be asking themselves this key question:

How can we achieve an acceptable level of accessibility when a course is being adapted from pre-existing materials?

While this can seem like an overwhelming task, it’s a vital one that we need to address and plan for. Let’s start by breaking down the topic a bit, so we can better assess our current levels of accessibility, and ultimately improve upon them.

Accessibility Guidelines

The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) provides useful techniques for making Web content accessible. The original 14 guidelines covered navigation, links, controls, images, menu, context, color, fonts, and language. They offered a way to design or revise existing content to make sites accessible for users employing the use of accessibility devices. The WCAG 2.0 guidelines take those original techniques and break them down into four main aspects for approaching accessibility, POUR, which stands for perceivable, operable, understandable, and robust. Each of these aspects describes testable success criteria to determine a site’s level of accessibility.

The challenge is how to make sure OER content, in all its diverse forms, provides an equal learning experience to all users. Ideally, this is handled by all platforms (in terms of navigation/graphical interfaces and audio and visual support) as well as with the resources and supplemental materials provided by instructors or institutions.

Platform Design

Many different platforms that are being used today for online learning; some well-known players are Blackboard, Canvas, OER Commons, Lumen Learning, Open EdX, and Pressbooks. Getting started with accessibility features in any of these platforms is in large part applying the guiding principles of WCAG.

For starters, accessible platforms need to offer the ability to use assistive technology devices, such as speech input software, screen readers, motion/eye tracking devices, and specialty keyboards for navigation. The interface should offer a logical, well-structured layout and hierarchy so that the site can be quickly and easily navigated. Layout and legibility, including the selection of appropriate fonts, color contrast, and ease of menu and link navigation, must be carefully considered.

Assessments

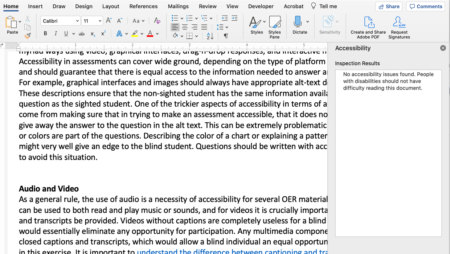

Accessibility in assessments can be a surprisingly complex topic, depending on the type of media (video, interactivity, etc.) or platform used for deployment. An accessible assessment item must provide equal access to any information needed to answer the item. This is where things can get tricky.

Keep in mind that any visual elements, such as graphical interfaces and images, must have appropriate alt-text descriptions, textual descriptions that provide visually disabled students with the same information a non-visually disabled student gleans from simply looking at the same visual. In writing accessible alt-text descriptions for assessment items, keep in mind that the description should provide only what a sighted student would gather from looking at the same image. Make sure the alt text does not provide interpretation of the image or give away the answer.

Audio and Video

Many OERs include multimedia. Screen readers can be used to both read and play music or sounds. But how to ensure that users with audio or visual disabilities can access the same course materials?

First off, all multimedia should include closed captions and transcripts. It is important to understand the difference between captioning and transcription. Although similar, captions mirror the spoken word, whereas transcripts offer a fuller “picture,” as they include the dialogue as well as descriptions, explanations, visual cues, etc. One way to understand the difference is to think of transcripts as being similar to play’s script. The script includes both the dialogue and the cues each actor needs to perform. Another key feature of transcripts is that they are searchable by the user, whereas captions are not.

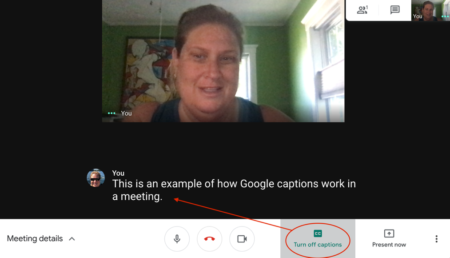

Captioning and transcripts are fairly simple to provide—or even create—for video that has been prepared ahead of a presentation or online lecture—i.e., for asynchronous teaching/learning. A bigger challenge is how to provide the same accessibility features for live video lectures, many of which include multiple remote participants. Enter live captioning, whether automated or manual. Here, too, course creators have options.

Live transcribers, such as those available through Communication Access Realtime Translation, or CART, use a stenotype machine with specialty software and a phonetic keyboard to type as words are spoken, thus providing closed captions in real-time. The downside of this is the price—the average rate for a CART captioner ranges from $50 to $75/hour. Not bad for a one-time need, but not practical for multiple classes a week over many weeks.

Fortunately, there are several free and open-source companies that use automatic speech recognition software (ASR) to provide live captioning. ASR is available for use on mobile devices, computers, and many conferencing platforms. For example, Google Meet offers ASR using Live Transcribe. Zoom also offers closed captioning, though the captions themselves must be typed by an assigned panelist or a host, making it both difficult and cost-prohibitive for many. Zoom does, however, accept the integration of third-party closed captioning services using an API—though use of this feature requires a subscription or purchase of this particular service. For institutions on a tight budget already, this might not be a practical or sustainable option.

RIP Snow Days

In 2005, when Hurricane Katrina devastated the city of New Orleans, it displaced an entire school system, leaving tens of thousands of students without access to education. The State of Louisiana responded by working with a coalition of private e-learning companies and charter academies to embrace online learning as one way to help bridge the gap until schools could be repaired, and students could return to the classroom. Similarly, in 2012, when Hurricane Sandy battered the NYC region, resulting in massive displacement of their student population, New York City Schools responded to the emergency by launching an e-learning initiative that would allow their student population to continue their education through virtual classrooms. But in 2020, when the Covid-19 global pandemic reached American shores and closed schools and universities across the country, the conversation looked quite a bit different, with everyone from The New York Times, Forbes, Wired, Medium, CNN, and many others putting forth their own opinions and predictions about what was in store for students.

Something we can all agree on is that the discussion around the role of online education has changed. What was once considered a life raft during times of emergency is now being recast as a central pillar. If the pandemic fundamentally changes our approach to public education, causing it to much more closely align to blended learning models that fuse in-classroom experiences with online learning, one question inexorably follows… Is this model of education available to everyone? Is it truly “accessible?”

Accessibility, in this context, means that the tools we use for online teaching are developed with inclusivity in mind, so that they can be used by as many people as possible, including those with impairments or disabilities. Designing a program from the ground up, with the intention to allow universal access to the greatest extent possible (i.e., adhering to the tenets of universal design leaning, or UDL), should be the goal of all virtual learning programs. This “ground-up” approach is preferable to retrofitting existing materials to meet accessibility guidelines.

Due to the sudden and unexpected nature of the COVID-19 crisis, many institutions attempting to ramp up their online offerings quickly have a limited budget, and as a result, may be more likely to turn to OERs. As these institutions build their fall course materials, they must also be asking themselves this key question:

How can we achieve an acceptable level of accessibility when a course is being adapted from pre-existing materials?

While this can seem like an overwhelming task, it’s a vital one that we need to address and plan for. Let’s start by breaking down the topic a bit, so we can better assess our current levels of accessibility, and ultimately improve upon them.

Accessibility Guidelines

The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) provides useful techniques for making Web content accessible. The original 14 guidelines covered navigation, links, controls, images, menu, context, color, fonts, and language. They offered a way to design or revise existing content to make sites accessible for users employing the use of accessibility devices. The WCAG 2.0 guidelines take those original techniques and break them down into four main aspects for approaching accessibility, POUR, which stands for perceivable, operable, understandable, and robust. Each of these aspects describes testable success criteria to determine a site’s level of accessibility.

The challenge is how to make sure OER content, in all its diverse forms, provides an equal learning experience to all users. Ideally, this is handled by all platforms (in terms of navigation/graphical interfaces and audio and visual support) as well as with the resources and supplemental materials provided by instructors or institutions.

Platform Design

Many different platforms that are being used today for online learning; some well-known players are Blackboard, Canvas, OER Commons, Lumen Learning, Open EdX, and Pressbooks. Getting started with accessibility features in any of these platforms is in large part applying the guiding principles of WCAG.

For starters, accessible platforms need to offer the ability to use assistive technology devices, such as speech input software, screen readers, motion/eye tracking devices, and specialty keyboards for navigation. The interface should offer a logical, well-structured layout and hierarchy so that the site can be quickly and easily navigated. Layout and legibility, including the selection of appropriate fonts, color contrast, and ease of menu and link navigation, must be carefully considered.

Assessments

Accessibility in assessments can be a surprisingly complex topic, depending on the type of media (video, interactivity, etc.) or platform used for deployment. An accessible assessment item must provide equal access to any information needed to answer the item. This is where things can get tricky.

Keep in mind that any visual elements, such as graphical interfaces and images, must have appropriate alt-text descriptions, textual descriptions that provide visually disabled students with the same information a non-visually disabled student gleans from simply looking at the same visual. In writing accessible alt-text descriptions for assessment items, keep in mind that the description should provide only what a sighted student would gather from looking at the same image. Make sure the alt text does not provide interpretation of the image or give away the answer.

Audio and Video

Many OERs include multimedia. Screen readers can be used to both read and play music or sounds. But how to ensure that users with audio or visual disabilities can access the same course materials?

First off, all multimedia should include closed captions and transcripts. It is important to understand the difference between captioning and transcription. Although similar, captions mirror the spoken word, whereas transcripts offer a fuller “picture,” as they include the dialogue as well as descriptions, explanations, visual cues, etc. One way to understand the difference is to think of transcripts as being similar to play’s script. The script includes both the dialogue and the cues each actor needs to perform. Another key feature of transcripts is that they are searchable by the user, whereas captions are not.

Captioning and transcripts are fairly simple to provide—or even create—for video that has been prepared ahead of a presentation or online lecture—i.e., for asynchronous teaching/learning. A bigger challenge is how to provide the same accessibility features for live video lectures, many of which include multiple remote participants. Enter live captioning, whether automated or manual. Here, too, course creators have options.

Live transcribers, such as those available through Communication Access Realtime Translation, or CART, use a stenotype machine with specialty software and a phonetic keyboard to type as words are spoken, thus providing closed captions in real-time. The downside of this is the price—the average rate for a CART captioner ranges from $50 to $75/hour. Not bad for a one-time need, but not practical for multiple classes a week over many weeks.

Fortunately, there are several free and open-source companies that use automatic speech recognition software (ASR) to provide live captioning. ASR is available for use on mobile devices, computers, and many conferencing platforms. For example, Google Meet offers ASR using Live Transcribe. Zoom also offers closed captioning, though the captions themselves must be typed by an assigned panelist or a host, making it both difficult and cost-prohibitive for many. Zoom does, however, accept the integration of third-party closed captioning services using an API—though use of this feature requires a subscription or purchase of this particular service. For institutions on a tight budget already, this might not be a practical or sustainable option.

The combination of captions, transcripts, and ASR offer several possibilities for live lectures.

Even so, some institutions may find these insufficient, and require the aid of a remote American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter, whose services can be used on nearly any Web-based conferencing or OER platform.

Supporting Materials

While the majority of OERs and MOOCs are accessible through virtual learning platforms, they don’t necessarily make up the entirety of teaching materials an instructor wishes to use for his or her course. Many courses are supplemented by various materials, such as secondary Websites, documents, PowerPoint slides, PDFs, etc.—all of which must also be made accessible.

Fortunately, many of these file types have native in-application accessibility checkers (common on both Adobe Acrobat and MS Office products). These in-app checkers allow educators to confirm the level of accessibility prior to use. They also offer suggestions on how to resolve any accessibility errors identified.

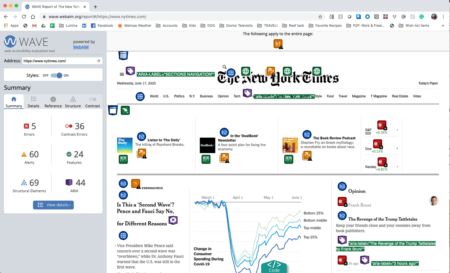

Websites can be check with one of the many free accessibility checkers, such as WAVE. These checkers confirm whether the proper structural hierarchy, metadata tagging, labels, fonts, and colors have been used in order to be navigable by screen readers.

Recommended Resources

As many institutions and individual instructors consider how their own courses must evolve to meet the needs of an increasingly remote—and diverse—student population, they must keep in mind the importance of materials that can be equally accessed by users of all types and abilities.

As Haben Girma, the first deaf-blind graduate of Harvard Law School and an advocate for equal opportunity, writes, “People with disabilities drive innovation.” Many of the technologies we take for granted today were created to solve a particular problem or to reach a wider audience. As always, we evolve—not just in terms of what we create, but also in how we share our creations.

0 Comments